From Struggle to Strength:

THE EARLY YEARS

1903 MEU

March 20, 1903 marks the registering of 'The Sydney Municipal Council Employees Union'- a new union to cover wage workers at the now City of Sydney Council.

This notice appeared in the New South Wales Government Gazette.

This notice appeared in the New South Wales Government Gazette.

The first formal meeting had been held the month before at Trades Hall, and the decision to form the Union was reported in The Worker.

This report appeared in The Worker on February 14, 1903.

This report appeared in The Worker on February 14, 1903.

In April, the decision to extend union coverage to workers at other suburban municipal councils was made.

This report appeared in The Daily Telegraph on April 29, 1903.

This report appeared in The Daily Telegraph on April 29, 1903.

On September 3, the Union's Secretary, James J. Hynes, wrote to the Lord Mayor and aldermen (councillors) requesting a meeting.

An extract of the letter from MEU Secretary James J. Hynes dated 3 September, 1903. (The file that includes this letter has been digitised by the City of Sydney Archives.)

An extract of the letter from MEU Secretary James J. Hynes dated 3 September, 1903. (The file that includes this letter has been digitised by the City of Sydney Archives.)

On September 4, Town Clerk T. H. Nesbitt replied:

'...as the writer of such a letter is not a member of the Corporation Service nor has the Lord Mayor any knowledge of the Union on behalf of which the letter is written the Lord Mayor sees no reason why the proposed conference should be held.'

In October, the Union passed a resolution and lodged a legal case against Council to improve working conditions.

In response, the Council's City Solicitor wrote to the Trade Unions Registrar in December requesting the cancellation of the Union's registration.

The letter drafted by the City Solicitor requesting the cancellation of the union's registration.

The letter drafted by the City Solicitor requesting the cancellation of the union's registration.

This request was considered by the Registrar, and refused in March 1904.

The 12 claims filed by the Union turned into a years-long legal dispute.

This report was published in The Daily Telegraph on September 30, 1904.

This report was published in The Daily Telegraph on September 30, 1904.

In preparing their case, Council requested, and the MEU provided, a full list of members of the Union.

The Council notated the occupations of each member and calculated there were 130 members in current service.

The Council notated the occupations of each member and calculated there were 130 members in current service.

The City Solicitor's case folder includes the MEU's pocket-sized book of rules, alongside the rule books for the 'Tip Carters' Union' and the 'United Laborers' Protective Society'.

The book of rules for members. The City Solicitor's file has been digitised by City of Sydney Archives.

The book of rules for members. The City Solicitor's file has been digitised by City of Sydney Archives.

The Council argued, in part, that the Union shouldn't have coverage over all the different kinds of workers doing council jobs, especially when there were other unions that could cover some of these workers.

This report was published in The Sydney Morning Herald on February 23, 1906.

This report was published in The Sydney Morning Herald on February 23, 1906.

This note appears on the City Solicitor's folder, marking the end of the case.

This note appears on the City Solicitor's folder, marking the end of the case.

On June 16, 1909 the first Award covering City of Sydney Council workers was made by a Wage Board. Wage Boards were introduced under a new industrial system in 1908.

The Award was published in the NSW Industrial Gazette in July 1909.

The Award was published in the NSW Industrial Gazette in July 1909.

The Award was a major MEU win that improved conditions for some wage workers, legitimising the Union in the process.

This report was published in The Worker on June 24, 1909.

This report was published in The Worker on June 24, 1909.

The Union was now able to advocate for individual members, with Council checking and correcting conditions against the Award as issues were raised.

City of Sydney Archives have digitised the file containing the MEU letters and internal correspondence following the 1909 Award.

City of Sydney Archives have digitised the file containing the MEU letters and internal correspondence following the 1909 Award.

A City of Sydney 'block boy' on Elizabeth St in 1909. (City of Sydney Archives: A-00037694)

A City of Sydney 'block boy' on Elizabeth St in 1909. (City of Sydney Archives: A-00037694)

Sydney Municipal Council staff picnic c1903. (City of Sydney Archives: A-00006253)

Sydney Municipal Council staff picnic c1903. (City of Sydney Archives: A-00006253)

Certificate of thanks for additional public holidays. (City of Sydney Archives: CC-000073)

Certificate of thanks for additional public holidays. (City of Sydney Archives: CC-000073)

1907 Clerks

On December 7, 1907 the first meeting of what would become the 'Federated Clerks' Union' was held.

This report on the first meeting was published in The Sydney Morning Herald on December 9, 1907.

This report on the first meeting was published in The Sydney Morning Herald on December 9, 1907.

The story told about the formation of 'The Clerks' centres on the actions of disgruntled clerk Arthur Jones.

“The immediate cause of the foundation of the Clerks’ Union was the excessive overtime worked in a certain city warehouse.

There had been 13 nights’ overtime — absolutely unpaid — in one month, and the clerks were in a state of rebellion.

One of them was Mr. A. A. Jones, who had as a clerk employed in a shop given evidence on behalf of the shop assistants before the Arbitration Court, and subsequently received the ancient and honorable order of the sack.

Mr. A. A. Jones was literally the founder of the Clerks’ Union. It was he who inserted an advertisement in the papers calling a meeting at the Queen’s Hall for the formation of a Clerks’ Union, and he bore the brunt of the inauguration.

The gathering was a very scanty one, and the confreres of Mr. Jones, although they had expressed their intention of joining, were conspicuous by their absence. The Union, however, was formed."

The need to form a union for 'sweated clerks' — sweated was the term used to describe being overworked and underpaid — was much debated in the press. Including through letters to the editor:

This letter to the editor was published in The Sydney Morning Herald on December 28, 1907.

This letter to the editor was published in The Sydney Morning Herald on December 28, 1907.

This former clerk wrote in to counter the argument outlined in a prior letter to the editor:

'It would be well for clerks to pause before joining the new union, because if the common rule under the Arbitration Act is made to apply to clerks, it will undoubtedly have the effect of placing the incompetent on a footing with the competent, and really make the minimum salary the maximum, thus barring the competent and ambitious clerk from advancement…’

'Would it not be much better for a definite minimum wage to be fixed than the miserable sweating that is almost universal?'

The landmark 'Harvester case' decision had just been handed down by Justice Higgins in the federal Arbitration Court, setting a minimum living wage for 'unskilled' workers.

The 'Harvester case' decision.

The 'Harvester case' decision.

In 1908, the 'United Clerks' Union' was registered.

This report about the registering of the union was published in The Sydney Morning Herald on April 10, 1908.

This report about the registering of the union was published in The Sydney Morning Herald on April 10, 1908.

“...The Union, however, was hampered by its lack of funds. It was unable to pay Mr. Jones anything more than a weekly payment for out-of-pocket expenses, and, to make matters worse, Mr. Jones suddenly found that he was the subject of a boycott by employers."

The passing of The Industrial Disputes Act (1908) would also prove less fortuitous for this union, with clerical workers not recognised as an industry under the Act.

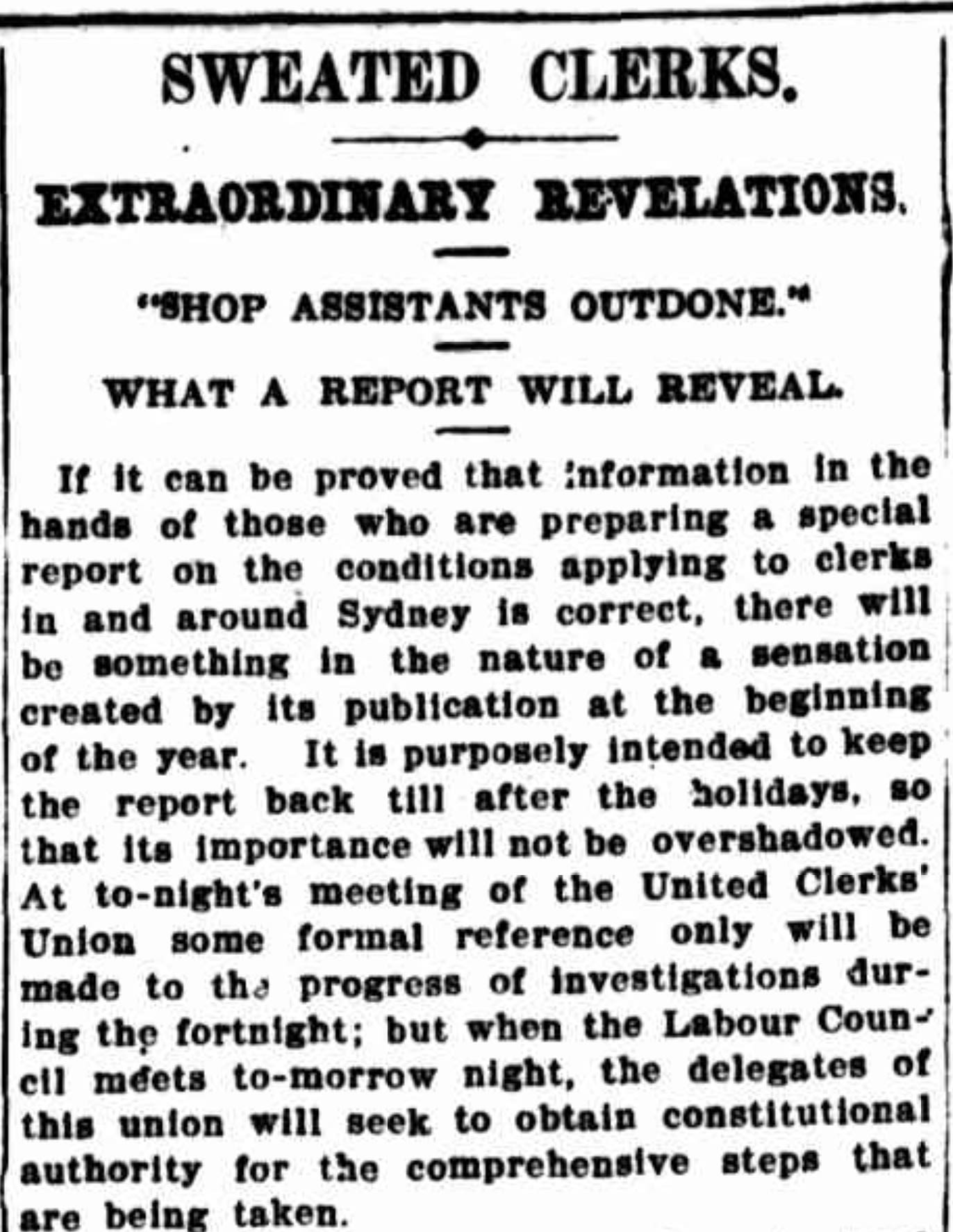

In the lead up to making a case for a Wages Board to cover all clerks, the Union canvassed the working conditions of clerks and produced a report.

This article was published in The Sydney Morning Herald on December 2, 1908.

This article was published in The Sydney Morning Herald on December 2, 1908.

On May 31, 1909, the Union's Wages Board application was denied.

This report on the Wages Board decision was published in The Sydney Morning Herald on June 1, 1909.

This report on the Wages Board decision was published in The Sydney Morning Herald on June 1, 1909.

In the first edition of the Union's periodical The Clerk, published in August 1909, the Union described their stoush with the state Industrial Court in boxing terms, saying:

'...only a few rounds have been fought yet'.

This pamphlet encouraging potential members to join the union is from 1909. (Sydney Trades Hall collection)

This pamphlet encouraging potential members to join the union is from 1909. (Sydney Trades Hall collection)

This report was published in The Worker on September 30, 1909.

This report was published in The Worker on September 30, 1909.

Women at work

At the 1908 Labor Women's Convention, the issue of Equal Pay was debated.

This report on the conference appeared in The Worker on November 26, 1908.

This report on the conference appeared in The Worker on November 26, 1908.

'... [Mrs. Dickie] was against sweating, but thought equal pay would displace them. Girls should not be compelled to marry for bread and butter.'

'... Mrs. Dwyer pointed out that this being a plank of the Federal Labor Party they could not alter it. (Dissent.) Women had been in the Federal Post Office on equal pay, and they had not been thrown out in consequence.'

'... Mrs. Leonard contended that no woman could do work of equal merit with a man. (Vigorous dissent.)'

'... The resolution was put and carried.'

1910s MEU

In February 1910, General Secretary George Ashton wrote to the Sydney Municipal Council Town Clerk, Thomas Nesbitt, telling him several Block Boys had not received the pay increase they were entitled to under the Award.

(City of Sydney Archives: A-00227978)

(City of Sydney Archives: A-00227978)

In April 1910, the Union changed its name to the 'Municipal Employees Union of New South Wales'.

The MEU commissioned a union banner, which was ready in time for Sydney's 8 Hour Procession in October 1910. The Union requested, and received:

'the use of a lorry and six horses to display the new "Banner" in the 8 Hour Procession'.

MEU Secretary Ashton's letter requesting the use of Council resources for the demonstration.

MEU Secretary Ashton's letter requesting the use of Council resources for the demonstration.

A Council memo in response to the request.

A Council memo in response to the request.

By 1912, the Union had expanded its coverage and set up regional branches across the state.

This feature on the MEU was published in an 'Eight Hour Souvenir' supplement in the Co-operator on October 7, 1912.

This feature on the MEU was published in an 'Eight Hour Souvenir' supplement in the Co-operator on October 7, 1912.

On November 27, 1913, the Union was re-registered as the 'Municipal and Shire Council Employees' Union of NSW'.

On January 1, 1915, the first edition of the Union's periodical The Counsellor was published.

The front page of the first MEU periodical The Counsellor, published January 1, 1915.

The front page of the first MEU periodical The Counsellor, published January 1, 1915.

On August 10, 1916, the Town Hall Branch was established to represent salaried workers in the Union.

This report on the Union Picnic was published in The Land on March 23, 1917.

This report on the Union Picnic was published in The Land on March 23, 1917.

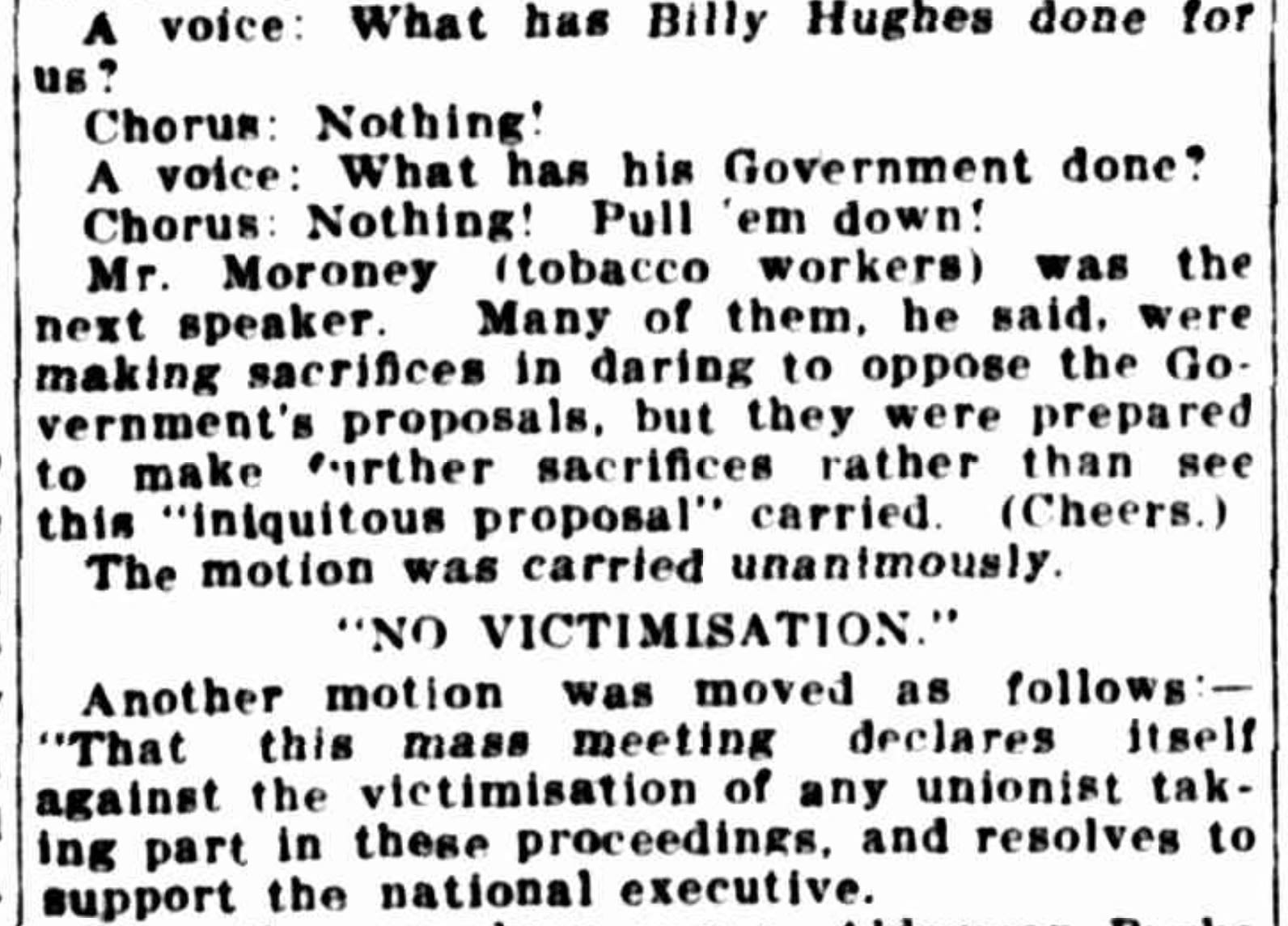

On October 4, 1916, the MEU participated in the city-wide stop work against conscription in the lead up to the first referendum at the end of October.

An article about the anti-conscription meeting was published in the Sydney Morning Herald on October 5, 1916.

An article about the anti-conscription meeting was published in the Sydney Morning Herald on October 5, 1916.

In July 1917, the Union became the 'Federated Municipal and Shire Council Employees' Union of Australia (New South Wales Branch)' to be in keeping with the name of the federal union.

A second conscription referendum was held on December 20, 1917.

The union's anti-conscription position was outlined in the December 1, 1917 edition of The Counsellor.

The union's anti-conscription position was outlined in the December 1, 1917 edition of The Counsellor.

In a feature piece about the anti-conscription campaign, President James Tyrell described this second majority 'No' vote as:

'...the greatest fight any community ever put up for Freedom...'

Published in the January 1, 1918 edition of The Counsellor.

Published in the January 1, 1918 edition of The Counsellor.

On George Ashton's death in 1918, James Tyrell became the Union's General Secretary. He would hold this position into the 1940s.

Organisers would visit the regional branches, and the 'Organiser's reports' would be published in The Counsellor.

Paddy Ross featured on the cover of The Counsellor, August 1, 1918.

Paddy Ross featured on the cover of The Counsellor, August 1, 1918.

As Organiser Paddy Ross made his way around the state on his motorbike, his reports also reflected the spread of the 'Spanish' influenza pandemic.

'As the 'flu is becoming prevalent in Lismore and surrounding districts and restrictions are being enforced, I will be unable to visit many gangs as the roads are a quagmire. I am leaving now for Grafton and Bellingen and other branches southward, and hope to return after the epidemic has been stamped out.'

'At Bingara I addressed an open-air meeting. Owing to the 'flu restrictions and as Mr. G. A. Clark was confined to his bed with the epidemic he was unable to attend, but I am pleased to state did all that was in his power to organise a meeting from a sick bed.

... At Barraba the staff has been retrenched, also at Gunnedah. [At] Liverpool Plains [I] also interviewed the shire clerk re Shire have left only four men to maintain 960 miles of roads.'

The MEU banner also toured regional NSW.

The MEU banner in Tamworth: The front page of The Counsellor, March 1, 1919.

The MEU banner in Tamworth: The front page of The Counsellor, March 1, 1919.

On June 20, 1919 the High Court handed down its decision in the “Municipalities’ Case”. The federal union had successfully argued that municipal councils should have access to the federal arbitration system. The court's consideration of whether an industry could exist at a federal level helped to pave the way for industry-wide awards.

The "Municipalities Case" High Court judgement.

The "Municipalities Case" High Court judgement.

The restored 1910 banner hanging in the Sydney Trades Hall atrium on March 29, 2023. It is the only banner held in the Sydney Trades Hall collection that was made by Henry Rousel's studio.

The restored 1910 banner hanging in the Sydney Trades Hall atrium on March 29, 2023. It is the only banner held in the Sydney Trades Hall collection that was made by Henry Rousel's studio.

Block boys at Hyde Park while landscaping works is being done, August 1916. (City of Sydney Archives: A-00037951)

Block boys at Hyde Park while landscaping works is being done, August 1916. (City of Sydney Archives: A-00037951)

City of Sydney staff during the 'Spanish flu' influenza pandemic, c.1918-1919. (City of Sydney Archives: A-00034797)

City of Sydney staff during the 'Spanish flu' influenza pandemic, c.1918-1919. (City of Sydney Archives: A-00034797)

A so-called 'widow cart', collecting rubbish in Manly, November 1919. (State Library of NSW: 93Qdeyl1)

A so-called 'widow cart', collecting rubbish in Manly, November 1919. (State Library of NSW: 93Qdeyl1)

Divers being supervised during extension works of a Council electricity generating plant at Pyrmont, August 5, 1913. (City of Sydney Archives: A-00039526)

Divers being supervised during extension works of a Council electricity generating plant at Pyrmont, August 5, 1913. (City of Sydney Archives: A-00039526)

A sinkhole in Redfern caused by a heavy coal load, April 12, 1918. (City of Sydney Archives: A-00015096)

A sinkhole in Redfern caused by a heavy coal load, April 12, 1918. (City of Sydney Archives: A-00015096)

The new MEU banner was displayed at this 8-Hour Day procession in October 1910. (City of Sydney Archives: A-00006712)

The new MEU banner was displayed at this 8-Hour Day procession in October 1910. (City of Sydney Archives: A-00006712)

The QVB in 1917, where the MEU office was located. (City of Sydney Archives: A-00041531)

The QVB in 1917, where the MEU office was located. (City of Sydney Archives: A-00041531)

Macdonell House, where the USU Sydney office is now located, on the sky line in 1918. (City of Sydney Archives: A-00040034)

Macdonell House, where the USU Sydney office is now located, on the sky line in 1918. (City of Sydney Archives: A-00040034)

1910s Clerks

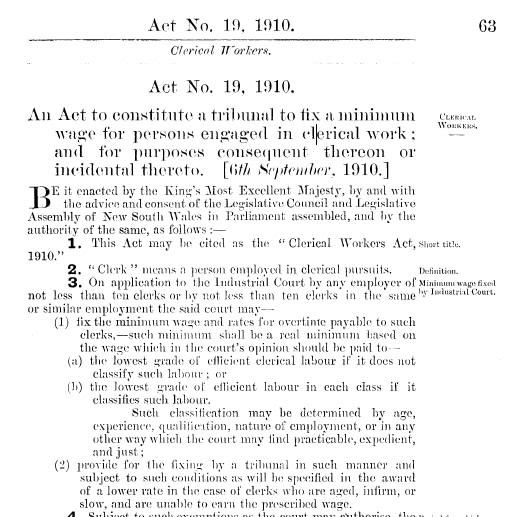

On September 6, 1910, the Clerical Workers Act (1910) became law. But this was no Wages Board that would bring with it government recognition of the Union.

The Union's position, as reported below, was that the Act was: "a legislative swindle", that "excluded the union" and "threw the onus of claiming improved conditions" onto clerks individually, even as it provided some recognition of the plight of clerks.

This report was published in The Sydney Morning Herald on September 20, 1910.

This report was published in The Sydney Morning Herald on September 20, 1910.

On April 13, 1911 the federal union, the 'Federated Clerks' Union of Australia' was registered.

The application to register the federal union was reported in The Sydney Morning Herald on March 6, 1911.

The application to register the federal union was reported in The Sydney Morning Herald on March 6, 1911.

On December 7, 1911, the Union appeared before the industrial court. With clerical workers introduced to the schedule of Industrial Disputes Act, the Union had made a new application for a Wages Board. This was hotly contested by employers arguing that the Clerical Workers Act should instead apply.

'The application was opposed by counsel representing the banks of issue in the county of Cumberland, the Sydney Daily Newspaper Employers' Association, the Underwriters' Association, the Incorporated Law Institute, and a large number of individual employers associated for the purpose.'

The court case was adjourned as there was a new industrial bill before parliament.

On April 15, 1912, the Industrial Arbitration Act (1912) again included no provision to recognise clerks as an industry.

In 1913, the ongoing temporary employment status for many public service clerks was a key union issue.

This report was published in The Sydney Morning Herald on July 24, 1913.

This report was published in The Sydney Morning Herald on July 24, 1913.

This article was published in The Daily Telegraph on May 20, 1913.

This article was published in The Daily Telegraph on May 20, 1913.

In 1914, the Union produced a report for the Premier about the shocking working conditions for city clerks.

This report was published in The Tamworth Daily Observer on March 30, 1914.

This report was published in The Tamworth Daily Observer on March 30, 1914.

This article continues:

'A plea is made for a regulated scale of wages for efficient female clerks, to make it unprofitable for employers to engage women, who are willing to work just for pocket money rather than do house work.'

On November 17, 1915, after parliament finally voted in favour of including clerks into the coverage of the new Act (after four unsuccessful attempts), the United Clerks' Union lodged a new application for a Wages Board.

On December 21, 1915, the Professional and Shopworkers’ Group, No. 9 (Clerks, Metropolitan) Board was established.

In 1916, an Award to cover metropolitan clerks was made.

The Award covering metropolitan clerks.

The Award covering metropolitan clerks.

This Award included a 'preference for unionists' clause:

'As between persons offering their labour at the same time, preference shall be given to the members of the United Clerks' Union, other things being equal.'

This request to Trades Hall for a meeting room to accommodate 130-150 members was made in September, 1916. (Sydney Trades Hall collection.)

This request to Trades Hall for a meeting room to accommodate 130-150 members was made in September, 1916. (Sydney Trades Hall collection.)

A certificate of appreciation addressed to Michael J. Connington is from the 'Inspecting staff' of the Municipal Council of Sydney's Health and Sanitary Department. (Sydney Trades Hall collection)

A certificate of appreciation addressed to Michael J. Connington is from the 'Inspecting staff' of the Municipal Council of Sydney's Health and Sanitary Department. (Sydney Trades Hall collection)

This certificate awards lifetime membership of the United Clerks' Union to Michael J Connington.

This certificate awards lifetime membership of the United Clerks' Union to Michael J Connington.

This profile on the union's founder appeared in The Australian Worker on November 20, 1919.

This profile on the union's founder appeared in The Australian Worker on November 20, 1919.

The 1917 'Great strike'

This article appeared in The Sun on August 29, 1917.

This article appeared in The Sun on August 29, 1917.

The 'Great Strike' which spread out from railway workers in 1917 was a formative period for many in the union movement in the subsequent decades.

This report was published in the Daily Advertiser on October 1, 1917.

This report was published in the Daily Advertiser on October 1, 1917.

This included Gavin Sutherland, who was MEU President from 1952-1967:

"I was a foundation member of the Letter Carriers’ and Postal Workers’ Union, got caught up in the 1917 strike, refused to load scab bags on the scab trains and I never went back to the Commonwealth Public Service."

Edna Ryan, who was a member of The Clerks in the 1920s and held leadership positions in the MEU in the 1960s and 1970s, including on the Executive, participated in the strike demonstrations as a teenager.

"You belonged to it if it was a strike. It was yours."

This is part one of 'The Early Years' timeline. We'll have more union history for you soon and throughout the year as we celebrate our 120th anniversary in 2023.

These two unions merged at a federal level in 1993 to form the Australian Services Union (ASU), and at a state level to form the United Services Union (USU) in 2003.

Not a USU member?

Join now to access expert advice and work alongside organisers, delegates and colleagues working to improve the conditions at your workplace.

Roadworks in the early 1930s. (City of Sydney Archives: A-00011330)

Roadworks in the early 1930s. (City of Sydney Archives: A-00011330)

Are you a NSW local council employee? We're your union.

We cover indoor and outdoor local council workers across the state.

Join here: usu.org.au/join/

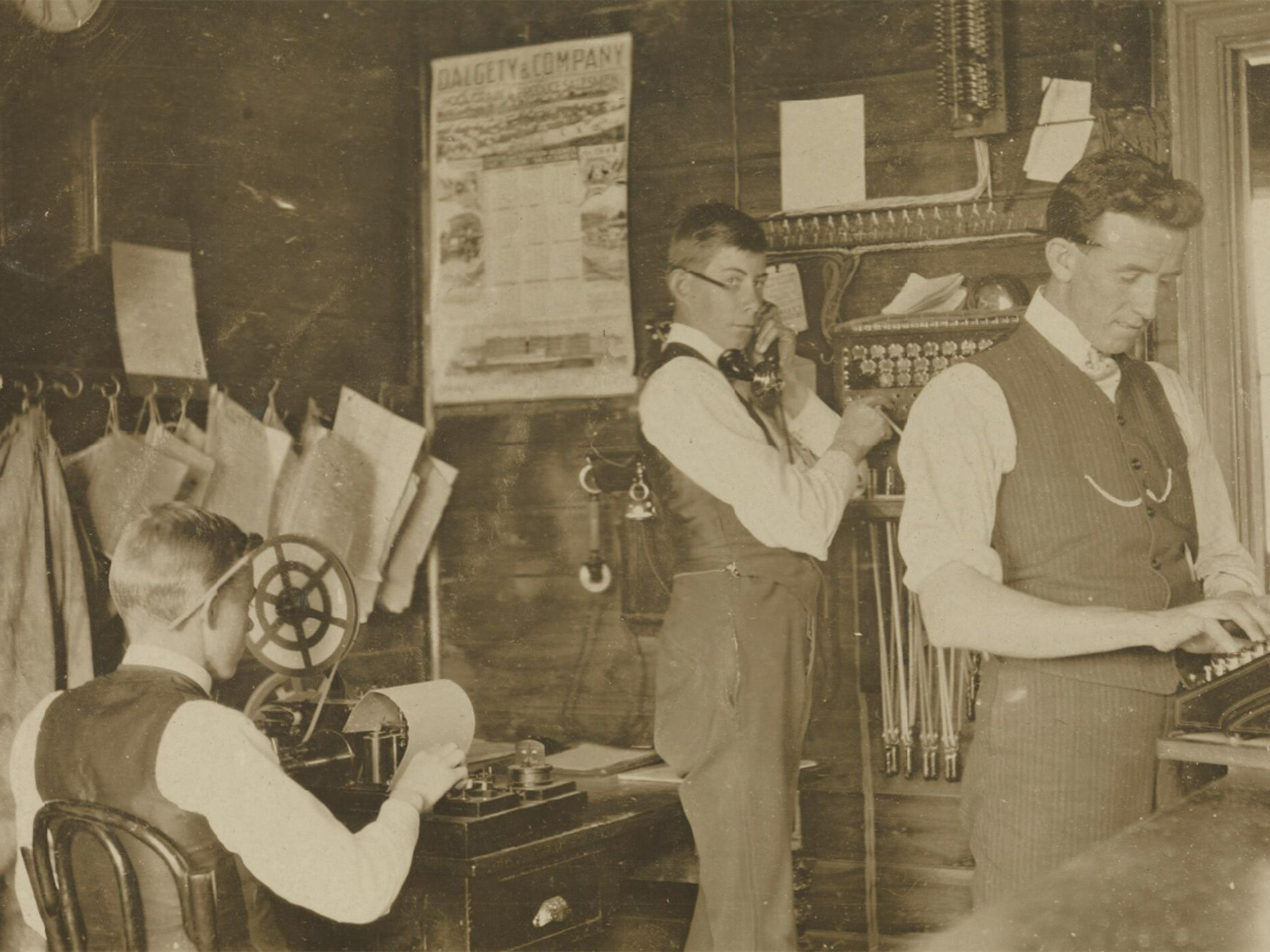

Music store workers c1905. (NLA: 4777372)

Music store workers c1905. (NLA: 4777372)

Are you a modern day 'sweated clerk' in NSW or the ACT? We're your union.

We cover employees in the private sector, as well as in the airlines, energy and utilities industries.

Join here: usu.org.au/join/

This timeline was produced on Gadigal and Wangal land for the USU's 120th anniversary celebrations in 2023.

Published on March 20, 2023. Authorised by USU General Secretary Graeme Kelly OAM.

—With thanks to City of Sydney Historian and USU member Laila Ellmoos, and the City Archives staff.

This timeline was updated on April 13, 2023 to add in the items from the Sydney Trades Hall collection, with thanks to Neale Towart and Bill Pirie.